Early management of adults with an uncomplicated first generalised seizure

د. حسين محمد جمعةاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2010

Learning outcomes

Upon completion of this module you should know:How to diagnose a patient with an epileptic seizure

What investigations you should perform

What treatment to start

When you can send a patient home

What advice you should give about driving

What follow up is necessary.

About the authors

MJG Dunn is a specialist registrar in Emergency Medicine and Intensive Care Medicine at the Emergency Department, The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.DP Breen is an ST1 doctor in Neurology at the Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh.

RJ Davenport is a consultant neurologist at the Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh.

AJ Gray is a consultant in Emergency Medicine at the Emergency Department in the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.

Why we wrote this module

"Suspected first ever generalised seizures in adults are common. There is a lack of consensus about the investigation, treatment, advice, and follow up of these patients. However, a review of the literature has enabled the formation of a clinical pathway for management in secondary care settings."

Introduction

Seizures are a frequent reason for attendance at emergency departments. It has been reported that 0.24-0.3% of adults who present to emergency departments do so because of a first seizure. Around 5% of the population will experience at least one non-febrile seizure during their lifetime. Various studies have looked at the investigation and management of first adult seizures but often no consensus has been reached. It has been proposed that treatment and referral guidelines should be agreed between emergency department staff and neurologists

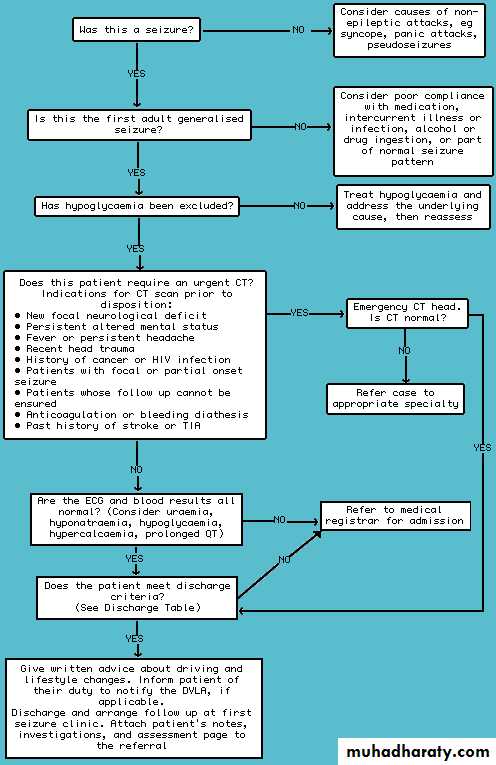

This review assesses the literature and formulates a clinical pathway (figure 1) for adults who present with a suspected first ever uncomplicated generalised seizure. Such a pathway is needed because, unlike epilepsy, where managed clinical networks and the Government Action Plan on Epilepsy Services are set to improve the standard of care in the UK, many emergency physicians differ in their approach to first seizures. This pathway should reduce variable management, streamline investigations and follow up, and avoid unnecessary admissions.

This pathway is not appropriate for patients with

Known epilepsySeizures related to head trauma

Seizures related to eclampsia

Status epilepticus.

• Figure 1 Algorithm for the management of adults with an uncomplicated first generalised seizure.

•

Differential diagnosis of seizures

Several conditions may mimic an epileptic seizure. A clear history from the patient, including eyewitness accounts where available, is crucial. The circumstances of the episode are important: sleep deprivation, acute alcohol or substance intoxication, and alcohol withdrawal are provoking factors for seizures. Loss of consciousness provoked by pain or other illness, or occurring during medical procedures (such as venepuncture or cervical smears) favours vasovagal syncope. One should consider three stages: before, during, and after the seizure.1. Before

Prodromal symptoms of seizures, if present, are often unusual and patients may find them hard to describe: they include déjà vu, stereotyped tastes or smells, and rising abdominal sensations.Presyncopal symptoms are usually more straightforward, including light headedness, nausea, clamminess, and "feeling faint." Pallor is typically seen in patients with syncope but its use in discriminating between epileptic and non-epileptic attacks has been questioned.

2. During

An eyewitness account should be sought to elucidate what happened during the unconscious period and the immediate aftermath - although myoclonic jerking, and even tonic-clonic movements may occur in patients with syncope.

3. After

Recovery of awareness after syncope is rapid(within 60 seconds), assuming patients have not had a secondary head injury. Patients usually recover without amnesia or confusion (although many patients will describe themselves as "disorientated" afterwards, what they usually mean is embarrassed or bewildered by what has happened).

Generalised epileptiform seizures usually are followed by a period of at least 10 minutes, and often more, of the post-ictal state, when patients are truly confused (often failing to recognise partners or family members), and while they appear conscious, almost always have amnesia for this period.

Asking about their first memory after the event is helpful: after a seizure it is usually in the ambulance or emergency department, whereas patients who have syncope have usually recovered long before the paramedics reach them.

Tongue biting is suggestive of a seizure, unlike incontinence, which is not specific and can occur in any type of collapse where the patient has a full bladder. Other symptoms such as headache and aching limbs are more suggestive of seizure than syncope.

The diagnosis of non-epileptic attacks, also known as pseudo-seizures or hysterical seizures, is difficult. They should only be confidently diagnosed by an epilepsy specialist. Staff may recognise attacks as atypical, but this is often unreliable and even experts are fooled.It may be helpful to carefully review the patient's psychiatric history where non-epileptic attacks are suspected. The safest policy is to assume that seizures are real until proved otherwise, or until the patient has been referred to a first seizure clinic.

Other conditions which can be misdiagnosed as seizures include:

• Hypoglycaemia• Cardiac arrhythmias

• Carotid sinus hypersensitivity

• Panic attacks

• Hyperventilation.

Learning bites

In a vaso-vagal attack there is typically:• Light-headedness

• Nausea

• Quick recovery.

Myoclonic jerks can often be seen in such attacks. In Lempert's study of medical students with syncope, myoclonic jerking occurred in 90% of subjects.

Some patients with seizures may have a short and transient period of paralysis after the seizure. This is known as Todd's paralysis.

Investigations

Blood tests

Various metabolic disturbances, including hypoglycaemia, hyponatraemia, and uraemia, can provoke seizures. Studies have found that 2.4-8% of patients have metabolic abnormalities associated with their first generalised seizure, but often these are clinically insignificant.

There is debate as to whether blood tests are of any value initially, with different studies offering different opinions. Many of these studies involve small numbers and are subject to type II error.

The current evidence suggests that routine blood testing will only reveal a small proportion of patients with significant metabolic abnormalities. However, these few abnormalities may influence management and the need for admission. We suggest that

testing for glucose, serum electrolytes, calcium, and full blood count is essential in the emergency setting, in combination with additional blood tests (such as blood alcohol) only if they are clinically indicated.

Learning bite

Examination is very important. For example you may find cafe au lait spots: these strongly suggest neurofibromatosis.Neuroimaging

Studies have quoted that up to 41% of adults have an abnormal CT scan following their first generalised seizure, falling to 6-10% if there are no focal neurological signs on examination.The American College of Emergency Physicians include neuroimaging as part of their evaluation of patients with first seizures.

Guidelines recommend brain imaging in all patients where a confident diagnosis of an idiopathic generalised epilepsy syndrome cannot be made There is a consensus that yield from scanning increases with age, and this has led to some physicians operating an age dependent policy with regard to neuroimaging. Lesions such as cortical atrophy and cerebral infarction account for most of the abnormal scans.

Many studies have suggested that neuroimaging is helpful in:

Making or excluding specific diagnosesQuantifying risk of recurrence

Guiding management.

Anyone, regardless of age, who has suffered a partial-onset seizure, or who has persisting focal neurological signs, requires neuroimaging.

The type of imaging has also been addressed. Most guidelines recommend magnetic resonance imaging over CT where resources permit.

Studies have found that MRI detects lesions that CT does not, such as:

• Mesial temporal sclerosis

• Cortical dysplasia

• Vascular malformations

• Some tumours.

Interestingly, it has been reported that patients are likely to have a better outcome if their intracranial tumour presents with a seizure rather than focal symptoms or signs. Tumours that are not obvious on CT scan are likely to be low grade gliomas.

There is a lack of consensus in the literature as to whether neuroimaging should form part of the initial management of an adult who has suffered a first seizure episode from which they have fully recovered. There appears to be a transatlantic divide, with US studies supporting the liberal use of neuroimaging and European guidelines recommending neuroimaging only in selected patient groups.

The decision that has to be made is whether the patient needs an emergency scan or whether this can wait to be performed as an outpatient. The indications for emergency neuroimaging are outlined in the algorithm. Initial neuroimaging is likely to be a CT scan as this is now widely available. If in doubt regarding the need for urgent neuroimaging, advice from local neurology services would be appropriate.

Learning bite

You should try to interpret the CT scan in the context of the clinical history. For example in a patient with a history of trauma you may see an extradural haematoma (a convex lesion) or a subdural haematoma (a crescent shaped lesion).NICE guidance recommends a CT brain scan should be performed and reported within one hour of request, for all patients with a post-traumatic seizure.

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network guidelines recommend an EEG in all young patients less than 25 years of age presenting with a generalised seizure. An EEG may also be helpful in supporting the diagnosis in older patients, but the EEG should not be used to exclude the diagnosis of epilepsyMany studies have found EEG to be useful in

Defining seizure type

Quantifying risk of recurrence

Quantifying likelihood of finding diagnostic abnormalities.

However, EEG has a 0.5-4% false positive rate and a relatively low sensitivity. Also, the positive predictive value of routine interictal EEG in a young healthy adult population is 2-3%.

As EEGs may be recorded at specialist units with long waiting lists, the impact on initial management is likely to be minimal.

An EEG is an unnecessary emergency investigation, and the decision as to whether it might be helpful should be made in a first seizure clinic.

Other tests

Patients with alcohol dependency can have a seizure as a result of:Excessive alcohol intake

Acute alcohol withdrawal

Complications of their alcohol dependency disorder

An underlying seizure disorder.

Alcohol intake >50 g/day (equivalent to >44 UK units/week) was found to be an independent risk factor associated with first generalised tonic-clonic seizures in a recent study. Indeed, alcohol has been implicated as a precipitating factor in up to one third of seizures. It would seem prudent to measure breath alcohol level as this may give a clue as to the cause. Measurement of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and mean cell volume may indicate chronic alcohol consumption.

An electrocardiogram (ECG) should be routinely performed as this is a cheap and non-invasive test which can detect other causes of collapse such as cardiac ischaemia and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Long-QT syndrome, which can present as a seizure, may also be detected.

Routine skull x rays and chest x rays are not appropriate unless there is a specific indication (for example head trauma or specific chest pathology).

Measurement of breath alcohol and an ECG should be routinely performed. Liver function tests and plain radiographs should only be ordered if there is a specific indication.

Treatment

Anticonvulsant medicationMost guidelines suggest that it is reasonable to recommend anticonvulsant treatment:

• If the patient has had previous myoclonic, absence, or partial seizures

• If an EEG shows unequivocal epileptic discharges

• If the patient has a congenital neurological deficit

• If the patient or physician considers the risk of recurrence to be unacceptable.

The risk of recurrence following a first unprovoked seizure varies substantially depending on the type of seizure, imaging, and EEG findings. Overall, the risk of recurrence is between 30-40%; this is greatest in the first six months and falls to <10% after two years. The First Seizure Trial Group concluded that the probability of long term remission was not influenced by treatment of the first seizure.

Many studies have agreed that anticonvulsant therapy should be withheld until a clearer epileptic pattern is established. However, neuroimaging, EEG, occupation, or the patient's opinion may influence this decision. The Medical Research Council Multicentre Study of Early Epilepsy and Single Seizure addressed this important issue. They found immediate treatment with anti-epileptic drugs reduced the occurrence of seizures in the subsequent one to two years but did not modify the rates of long term remission. Also, at two years the benefits of drug treatment were balanced by the unwanted side effects with no resultant improvement in quality of life.

Seizures provoked only by alcohol withdrawal, metabolic or drug-related causes, or sleep deprivation should not be treated with antiepileptic drugs. Patients should not be treated if there is uncertainty about the diagnosis.

Evidence indicates that anticonvulsant medication should only be prescribed to patients following their first generalised seizure when the risk of recurrence is particularly high. It is our opinion that prophylactic antiepileptic drugs should not routinely be started in the emergency setting, but only after consultation with a neurologist or other specialist with an interest in epilepsy.

Driving and lifestyle advice

Doctors should familiarise themselves with the laws relevant to their country of practice. In the UK, the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) states that following a first epileptic seizure, drivers who have group 1 entitlement (motor cars and motorcycles) should refrain from driving for one year with subsequent medical review before restarting driving. If they continue to drive, their motor insurance will not be valid.A doctor has a duty to advise patients of these facts and of the patient's duty to inform the DVLA. Doctors should keep a written record of the fact that this counselling has taken place. Audits of clinical records reveal that in only 0.9-21% of cases was it documented that such advice had been given. However, this may be artificially low as some patients may be non-drivers and others may have been given verbal advice without documentation.

Practitioners are probably also poor at informing patients about changes in lifestyle or occupation that would be prudent to make following an unprovoked seizure. Having had a single seizure should not materially affect most people's employment. If the job involves driving, working at heights, or working with machinery, there may be some restrictions.

In the UK patients should be advised to tell their employer that they have had a seizure in order to fulfil the requirements of Health and Safety at Work legislation. However, they are protected by the Disability Discrimination Act and their employer is expected to make reasonable adjustments in order to allow them to continue working. The Disability Discrimination Act applies to employers with 15 or more employees.

It is important to emphasise to patients that having a seizure should not stop them from doing the things they enjoy, although sensible safety precautions do need to be taken. For example, when swimming, patients should be accompanied by someone who is capable of managing a seizure. Lindsten recently reported that adults with a newly diagnosed unprovoked epileptic seizure become significantly less physically active, travel abroad less often, and are generally less active during their leisure time than sex- and age-matched controls.

Patients should be given verbal and written advice about driving and lifestyle changes prior to being discharged.

Discharge planning

US retrospective studies have used various criteria to determine the need for admission in adults presenting with a first seizure, often including a battery of tests.Results of tests were often predictable from history and examination clues. Ultimately only half of patients with new onset seizures unrelated to trauma, hypoglycaemia, alcohol, or drug use required admission.

One study advised admission for all patients quoting a high early recurrence rate. However, this is unlikely to apply to unprovoked seizures without neurologic deficit.

Many studies have agreed admission is probably only necessary:

• If the patient remains drowsy or comatose

• If a neurological examination reveals abnormalities suggestive of an underlying structural or treatable cause (for example meningoencephalitis)

• If the patient is at high risk of further seizures (for example alcohol withdrawal)

• If the patient cannot be supervised by a responsible adult.

Despite this, patients with a first seizure in the UK are often referred to the inpatient medical team, which is often unnecessary.

Following a first generalised seizure, adults who have fully recovered, have no neurological deficit, have normal initial investigations, have a responsible adult to stay with, and who are likely to attend outpatient investigations and follow up can be discharged from secondary care settings.

Follow up

Guidelines state that all patients with a suspected first generalised seizure should be followed up in a dedicated first seizure clinic.Davidson suggested that management of patients with definite or probable seizures depends upon the resources available but should ideally be provided by a physician with an interest in epilepsy.A consensus statement from the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh proposes that epilepsy must be a significant part of these consultants' clinical workload, equivalent to at least one session per week.

Follow up for adults with a suspected first ever generalised seizure should consist of consultation with an epilepsy specialist in a first seizure clinic, ideally within two weeks of presentation.

Conclusions

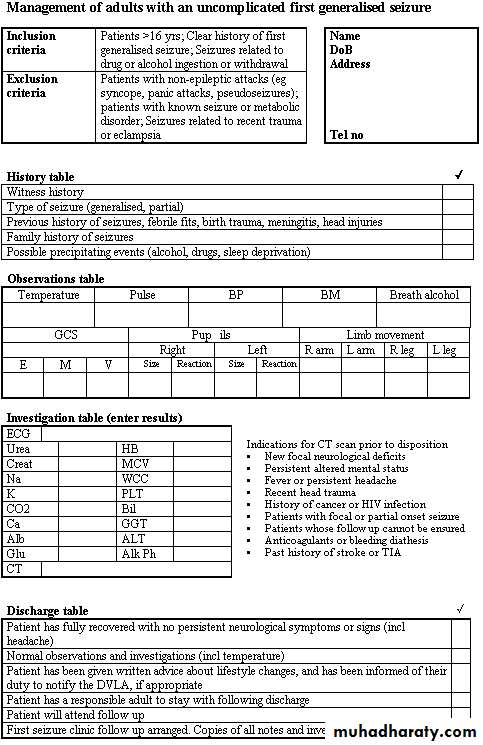

Although many studies have looked at various elements of management of a first generalised seizure in adults, there still seems to be a lack of consensus. A clinical pathway should not only streamline management but also avoid unnecessary investigations and admissions. This pathway is adapted to allow for local opinion as well as local resources but would apply well for many areas of the UK and other parts of the world. We would recommend that an adult with a first generalised seizure can be managed using the algorithm (fig 1) and data chart (fig 2) presented in this module.• Figure 1 Algorithm for the management of adults with an uncomplicated first generalised seizure.

•

• Figure 2 Data chart for the management of adults with an uncomplicated first generalised seizure.

•

A 21 year old woman comes to the Emergency Department as she has had a collapse. She also has a sore tongue.

Your answer

Correct answera.

Generalised seizure

b.

Complex partial seizures

c.

Vaso-vagal attack

What is the most likely diagnosis?

The tissue is split and is inflamed and bleeding slightly. A minor injury such as this generally requires no treatment. Tongue biting is strongly suggestive of a generalised seizure and is most often seen on the side of the tongue.

A 50 year old man has a seizure. He does not seek help immediately but comes to the Emergency Department two weeks later as he feels weak on one side of his face. On examination he is able to wrinkle up his forehead on both sides.

Your answer

Correct answera.

Todd's paralysis

b.

Bell's palsy

c.

Upper motor neuron facial palsy

• What is the most likely diagnosis?

•a : Todd's paralysis

Todd's paralysis would have resolved after two weeks.b : Bell's palsy

In someone with Bell's palsy the forehead would be weak as well.

c : Upper motor neuron facial palsy

This man has an upper motor neuron facial palsy. He may have an intracranial lesion.

A 60 year old man presents with a seizure. He undergoes a CT brain scan with contrast media.

Your answer

Correct answera.

Left posterior parietal meningioma

b.

Left posterior parietal extradural haematoma

c.

Left posterior parietal astrocytoma

d.

Left posterior parietal subdural haematoma

What is the most likely diagnosis?

a : Left posterior parietal meningiomaThere is a uniformly enhancing, extra-axial mass lesion measuring 5 cm x 2.5 cm in diameter in the left posterior parietal region. It contains some curvilinear calcification. There is little associated oedema but no midline shift. This is a left posterior parietal meningioma.

b : Left posterior parietal extradural haematoma

This is a left posterior parietal meningioma.

c : Left posterior parietal astrocytoma

This is a left posterior parietal meningioma.

d : Left posterior parietal subdural haematoma

This is a left posterior parietal meningioma.

Your answer

Correct answera.

A CT brain scan

b.

MRI brain scan

c.

Skull x ray

• A 40 year old man comes to see you as he has had a funny turn. You suspect that he has had a complex partial seizure. Which of the following investigations would you request?

•

: A CT brain scan

Studies have found that MRI detects lesions that CT does not.b : MRI brain scan

Studies have found that MRI detects lesions that CT does not, such as:

Mesial temporal sclerosis

Cortical dysplasia

Vascular malformations

Some tumours.8 21 27

Mesial temporal sclerosis often occurs in patients with complex partial seizures.

c : Skull x ray

Plain skull x rays are not indicated.

A 65 year old man is brought to the Emergency Department as he has had a fit. He is slow to regain consciousness and so has a brain scan. He has had no known history of trauma.

Your answer

Correct answera.

Extradural haematoma

b.

Normal scan

c.

Subdural haematoma

d.

Glioma

• What is the most likely diagnosis?

•a : Extradural haematoma

You would expect to see a convex shaped lesion in a patient with an extradural haematoma.b : Normal scan

This scan is abnormal.

c : Subdural haematoma

This cross section image of the brain is from a person who sustained a head injury. The injury resulted in bleeding beneath the dura mater. This is a subdural haematoma. Patients may have no history of trauma.

d : Glioma

This is not a glioma.

Your answer

Correct answer

a.

CT Brain

b.

Breath alcohol

c.

EEG

d.

ECG

e.

Serum electrolytes

• A 17 year old girl attends the emergency department following a witnessed fit. She had been out at a nightclub and was dancing when she let out a cry and dropped her drink. She fell to the floor, arched her back and became stiff with subsequent jerking of her limbs and head for a few minutes. This episode stopped spontaneously and she remained unconscious for 15 minutes. On arrival in the ED the patient was rousable but drowsy. She had no recollection of the fit and didn’t know how she came to hospital. She complained of a persistent severe headache and nausea but examination was unremarkable. Which investigation could WAIT until after specialist review?

•

a : CT Brain

An urgent CT Brain is indicated in those with persistent severe headache and drowsiness following a seizure (a spontaneous intracranial haemorrhage can present as a generalised seizure).b : Breath alcohol

Alcohol is implicated as a precipitating factor in up to a third of seizures.

c : EEG

Although the SIGN guidelines recommend an EEG for patients less than 25 with a generalised seizure, this is an unnecessary emergency investigation with a low sensitivity and a low positive predictive value.

d : ECG

Long QT syndrome may present as a seizure.

e : Serum electrolytes

Although the incidence of electrolyte abnormalities is low in those with a generalised seizure, finding an abnormal result may change your management.

Your answer

Correct answer

a.

Urinary incontinence during the event

b.

Rapid recovery of consciousness without confusion afterwards

c.

A collateral history of loss of consciousness with subsequent jerking of all limbs

d.

Pallor during the event

• A 32 year old man is referred to the acute medical assessment unit with a suspected first seizure from which he has recovered. Which of the following is most likely to suggest a epileptiform seizure?

•

a : Urinary incontinence during the event

Urinary incontinence during the event may occur as a result of any cause of loss of consciousness.b : Rapid recovery of consciousness without confusion afterwards

Rapid recovery of consciousness without confusion afterwards suggests a syncopal episode.

c : A collateral history of loss of consciousness with subsequent jerking of all limbs

The history including bystander accounts is the best discriminator of epileptiform seizures from non-epileptiform attacks. The diagnosis depends upon the whole story, before, during, and after the event, from both the patient and witnesses. All that shakes is not epilepsy.

d : Pallor during the event

Pallor during the event suggests either cardiac or non cardiac syncope, rather than a seizure.