Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding(AUGIB)

Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding is a common medical condition and an important gastroenterological emergency that results in high patient morbidity and medical care costs and can be fatal.Mode of presentation

(vomiting of blood) 1. Hematemesis :Red blood

or

Coffee-ground emesis

Frankly bloody emesis suggests moderate to severe bleeding that may be ongoing.

Coffee-ground emesis suggests more limited bleeding.

2- Melena: (black, tarry, offensive stool)

Melena may be seen with variable degrees of blood loss, being seen with as little as 50 mL of blood.3. Hematochezia ( is usually due to lower GI bleeding) can occur with massive upper GI bleeding , which is typically associated with orthostatic hypotension

Atypical presentation

Orthostatic dizzinessConfusion

Angina

Severe palpitations

These symptoms suggest severe bleeding

Major causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Common

Duodenal ulcer

Gastric ulcer

Esophageal varices

Mallory-Weiss tear

Less Common

Gastric erosionsEsophagitis

Dieulafoy lesion

Telangiectasias

Portal hypertensive gastropathy

Gastric varices

Neoplasms

Initial evaluation

The goal of the evaluation is:1. To assess the severity of the bleed.

2. Identify the underlying cause.

3. Determine if there are conditions present that may affect subsequent management (comorbidities)

History

1. Peptic ulcer-like symptoms.

2. Prior history of chronic liver disease.

3. Prior episodes of upper GI bleeding.

4. Drug history: aspirin and other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antiplatelet (clopidogrel) and anticoagulants.

5. Past medical history should be reviewed to identify important comorbid conditions that may influence the patient’s subsequent management.

Physical examination

1. Signs indicative of hypovolemia1. Resting tachycardia: Mild to moderate hypovolemia

2. Orthostatic hypotension (a decrease in the systolic blood pressure of more than 20 mmHg and/or an increase in heart rate of 20 beats per minute when moving from recumbency to standing) :

• Blood volume loss of at least 15 percent.

3. Supine hypotension: Blood volume loss of at least 40 percent.

2. Physical signs indicative of possible cause

- Stigmata of liver cirrhosis- Lymph node enlargement

- Mucocutaneous telangiectasia

- Epigastric mass.

- Abdominal signs of portal hypertension (ascites, splenomegaly)

3.Signs of significant co-morbid disease

1. Heartnfailure

2. Signs of chronic renal failure (CRF)

3. Signs of COPD

Laboratory data

1. A complete blood count2. Serum chemistries(urea, creatinine, electrolytes)

3. liver tests

4. Coagulation studies.

5. Serial electrocardiograms and cardiac enzymes may be indicated in patients who are at risk for a myocardial infarction, such as the elderly, patients with a history of coronary artery disease, or patients with symptoms such as chest pain or dyspnea.

Hemoglobin

1. The initial hemoglobin in patients will often be at the patient’s baseline and can be normal because the patient is losing whole blood.2. With time (typically after 24 hours or more) the hemoglobin will decline as the blood is diluted by the influx of extravascular fluid into the vascular space and by fluid administered during resuscitation.

3.The hemoglobin level is monitored every two to eight hours, depending upon the severity of the bleed.

Patients with acute bleeding should have normocytic red blood cells.

Microcytic red blood cells or iron deficiency anemia suggest chronic bleedingUrea-to-creatinine

Patients with acute upper GI bleeding typically have an elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN)Urea-to-creatinine ratio is high.

The higher the ratio, the more likely the bleeding is from an upper GI source

Nasogastric lavage

Advantages:

1. It confirms an upper GI source of bleeding.

2. Indicate ongoing bleeding and the need for urgent endoscopy.

3.. It can be used to remove food residue, fresh blood, and clots from the stomach to facilitate endoscopy

Lavage may not be positive if bleeding has ceased or arises beyond a closed pylorus

Treatment

1.General supportnothing per oral)) 1. NPO

2. Adequate vascular access: 2, 16 gauge or larger

caliber peripheral intravenous catheters or a central venous line should be inserted

4. Elective endotracheal intubation in patients with :

Ongoing hematemesis

Altered respiratory or mental status

To facilitate endoscopy and decrease the risk of aspiration.

2.Fluid resuscitation

Adequate resuscitation and stabilization is essential prior to endoscopy to minimize treatment-associated complicationsPatients with active bleeding should receive intravenous fluids (eg, 500 mL of normal saline over 30 minutes) while being typed and cross-matched for blood transfusion

If the blood pressure fails to respond to initial resuscitation efforts, the rate of fluid administration should be increased

ICU admission

Indications

1. Hemodynamic instability (shock, orthostatic hypotension)2. Active bleeding (manifested by vomiting of bright red blood , or hematochezia)

For :

1. Resuscitation

2. Close observation of:

Blood pressure

Electrocardiogram

Pulse oximetry.

3.Blood transfusions 3.

The decision should be individualized:1. Low risk patient(young adults without comorbid illnesses ): restrictive transfusion strategy (blood is given if HB below 7 g/dL)

2. High-risk patients (eg, older adults or those who have severe comorbid illnesses such as coronary disease or heart failure) should receive packed red blood cell transfusions to maintain a hemoglobin level of at least 10 g/dL.

3. Patients with active bleeding and hypovolemia may require blood transfusion despite apparently normal hemoglobin.

Care should be taken not to over-transfuse patients with suspected variceal bleeding, as doing so can precipitate worsening of the bleeding .

In such patients, we suggest a goal hemoglobin level of no greater than 10 g/dL

4. Pharmacotherapy

:1. Proton pump inhibitors (PPI)

Should be started at presentation and continued until confirmation of the cause of bleeding.

2. Vasoactive drugs (terlipressin or octerotide ):

Should be initiated as soon as variceal bleeding is suspected

Beneficial effects of PPI

PPI therapy also decrease the length of hospital stay, rebleeding rate, and need for blood transfusion in patients with high-risk ulcers treated with endoscopic therapyPPIs may also promote hemostasis in patients with lesions other than ulcers.

Value of acid suppressionAcid has been shown to inhibit platelet aggregation and even favors platelet disaggregation.

Acid is also known to facilitate clot lysis through the activation of pepsin, which occurs at pH levels below 2

The pH target required to avert these deleterious effects and favor hemostasis is thought to approximate 6.0 to 6.5

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Upper endoscopy :Early endoscopy (within 24 hours)

1. Diagnostic

2. Therapeutic

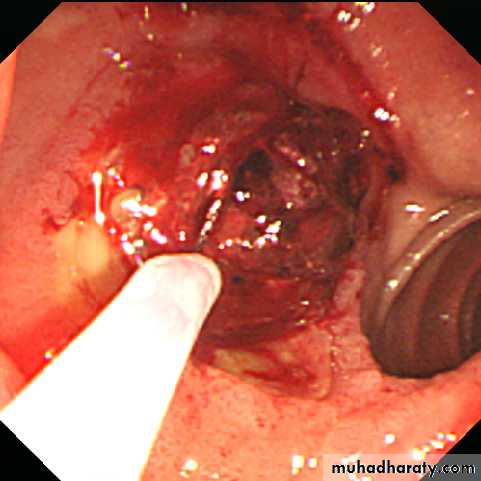

Bleeding peptic ulcer

The endoscopic appearance helps determine which lesions require endoscopic therapy

- Spurting hemorrhage

- Visible vessel

- Adherent clot

The absence of all of these stigmata identifies a subgroup of patients who can be discharged early from the hospital.

Forrest classification of bleedingpeptic ulcers

Grade Ulcer appearanceIa Spurting haemorrhage

Ib Oozing haemorrhageIIa Non-bleeding visible vessel

IIb Adherent clot

IIc Flat pigmented spot

III Clean ulcer base

Forrest JA, et al. Lancet 1974;17:394–7

Risk of re-bleeding by Forrest grade

Forrest I*

Forrest IIaForrest IIb

Forrest IIc

Forrest III

55

43

22

10

5

0

20

40

60

80

100

Patients with endoscopic or clinical re-bleeding (%)

Laine L & Peterson WL. N Engl J Med 1994;331:717–27*Patients did not receive endoscopic therapy

5.Endotherapy1. Bleeding PU: A variety of endoscopic methods have been described to control active bleeding from peptic ulcers. The most commonly used modalities are: a. Injection therapy(diluted adrenaline)

b.Thermal techniques (heat probes)

Endoscopic haemostasis

• Monotherapy with either epinephrine injection or thermal treatment (e.g. with a heater probe)

• or

• A combination of epinephrine injection plus thermal treatment and/or haemoclips

Epinephrine injection

Haemoclip

Heater probe

6.Surgery

Indications:Failure of endoscopic therapy

Hemodynamic instability despite vigorous resuscitation (more than a three units transfusion)

Recurrent hemorrhage after initial stabilization (with up to two attempts at obtaining endoscopic hemostasis)

Continued slow bleeding with a transfusion requirement exceeding three units per day

Esophageal varices

1. Pharmacological therapy

Using vasoactive drugs should be initiated as soon as :variceal hemorrhage is suspectedTerlipressin should be the first choice

Octerotide infusion is an alternative option

2. Endotherapy

Endotherapy should be done as soon as possible under resuscitation, preferably within 6 h of admissiona. Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL )with multiband ligator is the treatment of choice for acute esophageal variceal bleeding

b. Injection sclerotherapy (EST) is indicated EVL is not available or is not technically feasible

.

3. Sengestaken tube

Balloon tamponade (Sengestaken tube) should only be used in uncontrolled bleeding as a temporary ‘‘bridge’’until definitive treatment can be instituted for a maximum of 12 hrs.This technique employs a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube possessing two balloons which exert pressure in the fundus of the stomach and in the lower oesophagus respectively

3. Transjugular intrahepatic portovenous shunt (TIPS)

This technique uses a stent placed between the portal vein and the hepatic vein within the liver to provide a portosystemic shunt and therefore reduce portal pressureIndications:

1. Persistent variceal bleeding

2. Rebleeding

Despite combined pharmacological and endoscopic therapy

4. Portosystemic shunt surgery

Surgery prevents recurrent bleeding, but carries a high mortality and often leads to encephalopathy5. Antibiotics

Bacterial infections are present in up to 20 percent of patients with cirrhosis who are hospitalized with gastrointestinal bleeding and up to an additional 50% develop an infection while hospitalized.Such patients have increased mortality.

Emergency management of bleeding varices

Management

Reason

i.v fluids (1-2 L)

Extracellular volume replacement

Vasopressor (terlipressin)

Reduces portal pressure, acute bleeding and risk of early rebleeding

Prophylactic antibiotics (cephalosporin i.v.)

Reduces incidence of SBP

Emergency endoscopy

Confirm variceal rather than ulcer bleed

Variceal band ligation

To stop bleeding

Proton pump inhibitor

To prevent peptic ulcers

Phosphate enema and/or lactulose

To prevent hepatic encephalopathy

Prevention of recurrent P.U bleeding

Depend on the eitiology of ulcer:1. H. pylori is eradicated and after cure is documented anti-ulcer therapy is generally not given.

2. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

are stopped; if they must be resumed low-dose COX-2-selective NSAID plus PPI is used.

3. Patients with established cardiovascular disease who require aspirin should start PPI and generally re-institute aspirin soon after bleeding

ceases (within 7 days and ideally 1 – 3 days).

4. Patients with idiopathic ulcers receive long-term anti-ulcer therapy